“There are so many people struggling with staying alive.”

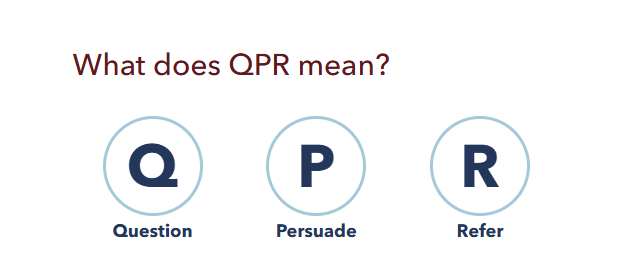

QPR stands for Question, Persuade, and Refer. It’s an algorithm that equips anyone with the ability to prevent suicide. Question means asking directly if someone is suicidal. Persuade means persuading someone to stay alive and accept help. Refer means actively connecting someone to that help, including their own therapist or support team.

I recently completed my training, remotely and for free, with the ADAMHS Board of Cuyahoga County, here in Ohio. ADAMSHS (Alcohol, Drug Addiction, and Mental Health Services) Boards are independent political subdivsions of the State of Ohio. They offer a wide range of mental health and addiction recovery services and trainings. Summit County (where I’m actually located) has a local board. No matter where you live, you should know about your local resources. It can save your life and others. That responsibility is especially acute for educators who regularly engage with young adults, among whom suicide remains a leading cause of death.

There is another QPR training coming up on April 8 if you are interested.

If you’ve been following me on social media recently, you’ve probably seen that I’ve been talking a lot about suicide. Which, according to my training, is a sign someone is contemplating it. I’m not. Not currently. But to the detriment of ever completing my first article, I’m working on a new one about suicide and technology. So, I’ll be talking a lot about suicide, and I think more people should be talking about it too.

This project is especially hard because it touches public health. I’m not a public health expert. I’m a technologist who studies robot brains (which make more sense to me than my own), and a law professor who fights to preserve our right to talk about uncomfortable stuff, like suicide. I’m approaching my research with care, trying to be a good steward of something both monumental and devastating, and learning everything I can while recognizing my own history of battles fought, battles won, and battles I almost didn’t survive.

Beyond my research, I also completed QPR training because I work with a large community of students (mostly young adults) in a high-pressure environment that predictably amplifies anxiety, depression, isolation, impostor syndrome, and the like. All of these are risk factors for suicide. QPR training does not make you a counselor. I am not licensed to provide therapeutic services of any kind. What it does do is heighten your awareness of crisis and suicide risk, and give you a simple, easy-to-remember framework for recognizing when someone may be at risk of dying by suicide, and for helping them pause, even briefly, long enough to accept professional help. QPR is all about noticing, actively listening, empathizing, and supporting someone in crisis. These are skills everyone should have.

Suicide is a complicated mix of risk factors and neural drama, some of which we kind of understand, and a lot of which we don’t. Our discomfort lies mostly in the latter. Most terrifyingly, the mind is not always a safeguard. When it fails, or turns inward, destroying us or those we love, we are forever left with unanswerable questions, a door that never truly closes. We don’t talk about it, because that forces us to confront it. For example, parents often miss signs that their children are suicidal, not because they are not paying attention, but because they cannot physically bear the thought that their child could be experiencing something so dark and painful. The other reason we don’t talk about suicide is probably because of the unnerving truth that the call of the void is, at some level, familiar.

And yet, according to the QPR Institute, talking about it is the most important thing we can do to keep ourselves and each other alive.

The makeup of the class itself was notable. My classmates included social workers, concerned parents and spouses, and people quietly navigating their own mental health battles. I entered as a researcher. By the end, I felt far closer to the self-help seekers.

Our instructors first asked us each to share what our impressions were of suicide. Some said sucide is a mental illness. Some said that suicide is attention seeking behavior. One said that they were raised to believe you go to hell for “committing” suicide; another recalled hearing “our family doesn’t do that.” Others described suicidal people as crazy, mental, or weak. My classmates didn’t agree with these views, but they heard them, were raised on them, or were taught them at one point or another.

The point of the exercise was to expose the stigma surrounding suicide. How we talk about suicide matters. One of the primary reasons people who are suicidal do not seek help is fear of judgment. That fear is rooted in a long and ugly history of how suicidal people have been treated.

Take language. We no longer use the phrase “committed suicide” because committed comes from a time when suicide was criminalized. People who attempted suicide were punished. The families of those who died by suicide were punished. Suicide was treated as blasphemy—a crime against oneself and against God. Those who died by suicide were deemed sinful and unclean, and were denied burial with their families or communities. Many were buried at crossroads as a deliberate act of public condemnation meant to mark the suicide as unforgivable.

We have made real progress in how we speak about suicide. But we have also reinvented stigma in new forms. Today, conversations about suicide, particularly in the context of technologies like chatbots, are saturated with the language of “defect” and “danger.” While we no longer imprison or fine suicidal people and their families, we continue to treat the expression of suicidal thoughts as something illicit. Suicidal speech is framed as a malfunction to be eliminated. And when we insist on punishment merely for allowing these conversations to exist, the message to people seeking help through technology is that they, too, are defective.

Our instructors emphasized, again and again, that suicide is complicated. There is no single cause, only a constellation of risk factors. Everyone can play a role in prevention, because suicide is everyone’s problem. A diagnosis of mental illness is not destiny; while it may operate as a risk factor, not everyone with a mental illness is suicidal. At the same time, not everyone who dies by suicide had a diagnosable mental illness at all (which is scary on its own because it can happen to any one of us). Our instructors emphasized that people think about suicide far more often than we like to believe.

Despite that, suicide is among the most preventable causes of death when there is early intervention. That’s where QPR comes in.

A few points stood out as both personally striking and central to my research.

- Asking someone directly whether they are suicidal reduces their anxiety by making them feel seen. People who are suicidal often want to talk about their thoughts but don’t know how to begin, are worried about being judged, or hesitate because they fear burdening the person they’re speaking to. Asking the question first relieves that pressure, and opens the door.

- People miss warning signs—and miss opportunities to save lives—because they are uncomfortable asking the question. This point was taken so seriously that, at the end of the class, our instructors had us all unmute and repeat, together, the question: “Are you thinking about killing yourself?” to become more comfortable and to sit with it.

- People avoid asking the question not only because it is uncomfortable, but because they fear the answer. Many simply do not know what to do with a suicidal person once the truth is spoken. Again, this is the point of QPR. This reminded me of a phenomenon I’ve heard repeatedly from friends who have battled cancer, or who have loved someone who has. Cancer patients often lose friends, not out of cruelty, but out of fear. People don’t know what to say, how to act, or how to sit with something so serious and frightening. So they pull away. The result, in both cases, is isolation at precisely the moment connection matters most.

These points kept pulling me back to a simple question: why people experiencing suicidal ideation are increasingly turning to chatbots. Our instructors emphasized that practicing QPR effectively requires availability, time, courage, and deep empathy. You have to be present. You have to stay with someone for “as long as it takes” to slow the crisis and persuade them to accept help. You have to be willing to ask the hardest questions, and you have to do it without judgment.

A chatbot can do all of those things. Chatbots are always available. They have unlimited time. They can be trained on QPR strategies to widen the lens of someone in crisis, to talk through options, and to encourage help-seeking. Chatbots are fearless. They can ask the hard questions. And they can do it in a way that feels nonjudgmental—because bots do not judge, and, crucially, people know that.

And yet, this is precisely where regulatory instincts seem to fail. The prevailing policy response to expressions of suicidal ideation seems to be silence. Chatbots should not engage at all, or should immediately deflect to a hotline. Social media services should remove suicidal speech and ban accounts that continue to express it.

But if talking about suicide is one of the most effective ways to prevent it—as QPR training teaches—then these approaches seem harmful. Imagine someone who has reached the point of expressing suicidal intent to a chatbot, only to be told they are “violating” the system. At the exact moment when that person needs calm, nonjudgmental engagement and de-escalation, they are met with rejection. They are told their distress is wrong, their thoughts are unacceptable, and possibly even banworthy.

People living with suicidal thoughts already believe they cannot be helped. When we build systems that refuse to engage, or when we take the resource away entirely, we tell them they were right. There is no one left to talk to. Not even a robot.

I don’t mean to suggest that chatbots should replace therapists or other mental health professionals. I’m approaching this from a harm-reduction perspective that recognizes that when someone is suddenly in crisis, time matters, and people reach for what feels safest and most accessible in that moment. As the headlines are showing us, that will likely be a chatbot like ChatGPT.

If generative AI can be thoughtfully trained on the same QPR framework we are taught—”listening” without judgment, asking direct questions, slowing the crisis, and encouraging professional help—then it has the potential to save lives. In fact, given its constant availability and ability to meet people where they are, it may be able to reach people that none of us ever could. That possibility is extraordinarily valuable. It is precisely why we should be careful about regulatory approaches that force chatbot developers to default to silence, deflection, or prohibition.

The last point that really stuck with me from the training was this one:

Teachers occupy an outsized role in the lives of many young people. For some students, the loss of a teacher can feel as destabilizing as the loss of a parent. That rupture can place them at heightened risk of suicide when a trusted adult is suddenly gone. I sat with that reality for a long time. It forced me to think carefully about my own relationships with my students, about who I am in their lives, and what it means for me to be someone they trust.

The role of an educator is already critical. But knowing this raises the stakes. It places a profound responsibility on us to show up as steady, trustworthy presences and to recognize that for some students, we are not just instructors, but lifelines. That is not a role we can afford to take lightly.

That, to me, is why I think all educators, especially law professors, should get QPR trained. It’s free, it’s online, and doesn’t take that much time. I will be urging my colleagues to consider it. There is free class coming up on April 8 at 10am ET if you’re interested.

The R in QPR means Refer. We learned that while we may not be able to solve the problems that a person struggling with suicide is facing, we can be brokers of information. Our instructors included (along with the crisis hotline / textlines) the following resources: NAMI, AAS, the National Action Alliance for Sucide Prevention, and the Trevor Project. Knowing about the resources available and actively connecting people to those resources saves lives.

Our class ended with a final point:

“It’s okay to not be okay. It’s not okay to not ask for help.”

If you or someone you love is struggling right now:

- Call or text 988 to reach the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline (U.S.). You’ll be connected to a trained counselor, 24/7, for free and confidential support.

- Text HOME to 741741 to reach the Crisis Text Line if speaking on the phone feels like too much. A trained crisis counselor will text with you in real time.

- Call 911 if you are in immediate danger or believe someone’s life is at risk.

You are not a burden. You deserve to be heard. And help is available.

Leave a comment