My students often ask me why we aren’t talking about this. As a new professor, I’ve only seen a few versions of this. This meant what’s happening in Gaza. This meant the reelection of Donald Trump. This meant the assassination of Charlie Kirk. This meant the mass censorship of late-night television. And now this means the brazen killing of Americans by their own government. With every version, I must ask whether speaking honestly about this will have me targeted, fired, or killed.

Today, I once again find myself the day before class wondering whether and how I address this. I think all educators would agree that our priority is our students. Some suggest, then, mentioning only news that is relevant to the subjects we’re teaching. And while I think, at a glance, that sounds right and fair, I can’t make sense of it for law professors. What aspects of our crumbling rule of law are “relevant” to the pursuit of knowledge and truth about it?

Teaching in a red-state institution turns this into a high-risk calculation. Our students differ from us — and from each other — along political and ideological lines. I don’t think that alone should deter us from acknowledging moments like this. But I recognize the stakes are higher when those differences are real and present.

The classroom is sacred ground. The relationship between students and professor is built on duty and trust. My duty is to meet my students’ educational needs, and often needs that go beyond the syllabus. My students, in turn, trust me to exercise that power responsibly. But that same relationship is also freighted with anxiety about bias and favoritism, which is only amplified in classes governed by a mandatory curve.

It is that power imbalance that creates real tension for professors who want to acknowledge the atrocities unfolding outside the classroom without placing students in a position where disagreement could feel professionally dangerous. If anxieties about something I’ve said creates an obstruction for learning the materials I’m charged with teaching, then I’ve failed my duty as an educator to my students.

And yet, refusing to speak about this creates its own breach of trust. As a law professor, I’m expected to show how the doctrine I teach operates in the world my students are about to enter. Marching through case law as if it exists in a vacuum, while the people who write, interpret, and enforce that law are actively abusing their power to hollow it out, seems like academic malpractice. Doing so asks students to accept a version of the law that bears little resemblance to reality. Which, in plain terms, is just another flavor of institutional gaslighting.

Our silence also normalizes this. If we do not teach our students that the government cannot kill them or their clients for lawfully exercising their rights, then we are quietly training them to accept unchecked state violence as a background condition for the practice of law. Perhaps worse, our silence falsely suggests there are two defensible sides to the rule of law. There are not. There is no “getting to maybe” when it comes to our basic freedoms.

Not to mention, red states designed this to be politically fraught so that silence is no longer a matter of classroom decorum, but of self-preservation. And as more of them pass laws meant to police how professors teach the law, the question of why we aren’t talking about this isn’t a hard but dangerous one to answer.

Maybe we aren’t talking about this because the state has decided that naming reality counts as “indoctrination.” Maybe we aren’t talking about this because we have watched other institutions discipline, investigate, and push out professors for doing exactly that. Or maybe we aren’t talking about this because newly imposed state accreditation standards can be invoked to threaten our students’ degrees and futures.

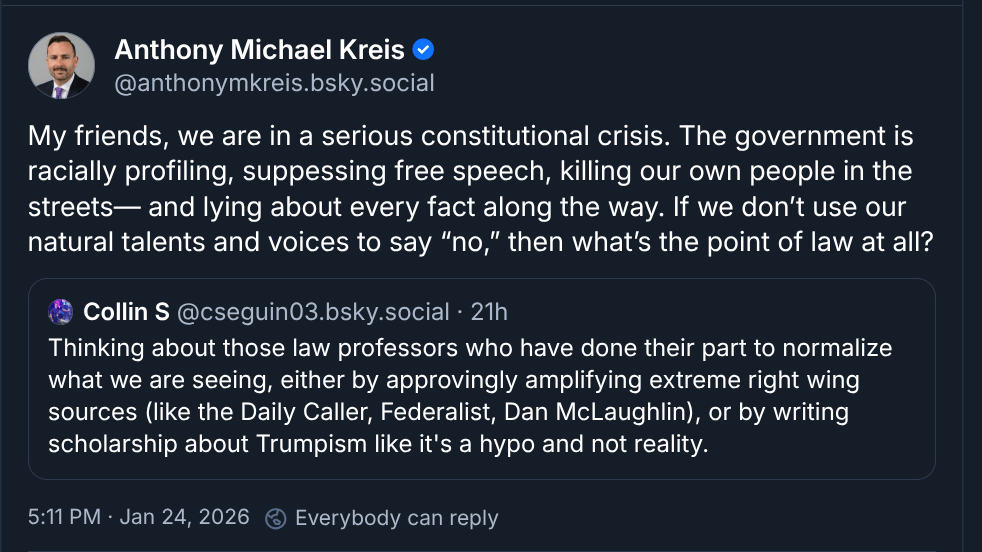

I offer these thoughts not as pushback to the students who ask why we aren’t talking about this. It’s a critical question that they should keep asking. Rather, I offer them as a tiny sliver of insight into the existential crisis looming over academia at large. That’s not a problem I can solve today. But let me say this in no uncertain terms:

The government killed Renée Good — a wife, a mother, a human being — shot to death by a federal agent during an enforcement action in Minneapolis earlier this month. The government killed Alex Pretti — a father, an ICU nurse, a human being — shot and killed by federal agents in the same city amid protests against that very enforcement operation.

The fact that they were American citizens shouldn’t even be necessary to note. They were people, lawfully present, lawfully exercising rights on American soil. I include their citizenship simply as a warning to those of us who still cling to the illusion of “belonging” here.

This should not have happened. This should not be happening. This is not normal. This is not what a functioning democracy looks like. This is not how the rule of law operates. It is relevant to every subject taught in law school and to every area of legal practice. And it is a constitutional crisis that all of us should be confronting openly and urgently.

Leave a comment